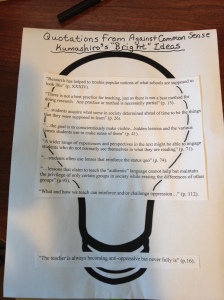

I chose a picture of a light bulb to represent what I thought were the best quotations of Kumashiro. Here are the quotations as well, just in case they are not showing up well on my picture.

The stem is the key idea or theme that I thought recurred throughout the book. The light bulb portion contains quotations that support or help “brighten” this recurring theme. Here are the quotations as well, just in case they are not showing up well on my picture.

Light bulb part:

“Research has helped to trouble popular notions of what schools are supposed to look like” (p. XXXIV).

“There is not a best practice for teaching, just as there is not a best method for doing research. Any practice or method is necessarily partial” (p. 13).

“…students acquire what some in society determined ahead of time to be the things that they were supposed to learn” (p. 26).

“…the goal is to conscientiously make visible…hidden lessons and the various lenses students use to make sense of them” (p. 41).

“A wider range of experiences and perspectives in the text might be able to engage students who do not normally see themselves in what they are reading” (p. 71).

“…students often use lenses that reinforce the status quo” (p. 74).

“…lessons that claim to teach the “authentic” language cannot help but maintain the privilege of only certain groups in society while erasing the differences of other groups” (p.95).

“What and how we teach can reinforce and/or challenge oppression…” (p. 112).

Stem:

“The teacher is always becoming anti-oppressive but never fully is” (p.16).